October 12, 2015

The first witness in the court proceedings supporters and attorneys believe will free the Fairbanks Four was William Holmes, who calmly took the stand and confessed to the crime for which the four men have served the last eighteen years. He was followed by a litany of powerful witnesses who bolstered his claim. It was difficult to imagine a witness that may prove more damaging to the state’s case than Holmes. But perhaps the most powerful testimony, and the testimony most damning to the state’s insistence that the Fairbanks Four are guilty may have come today from two cold case detectives who set out to investigate the case on behalf of the state.

The first witness in the court proceedings supporters and attorneys believe will free the Fairbanks Four was William Holmes, who calmly took the stand and confessed to the crime for which the four men have served the last eighteen years. He was followed by a litany of powerful witnesses who bolstered his claim. It was difficult to imagine a witness that may prove more damaging to the state’s case than Holmes. But perhaps the most powerful testimony, and the testimony most damning to the state’s insistence that the Fairbanks Four are guilty may have come today from two cold case detectives who set out to investigate the case on behalf of the state.

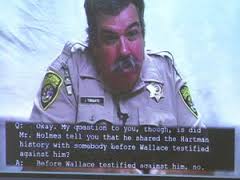

Troopers Gallen and McPherron worked directly under prosecutor Adrienne Bachman from late 2013 until their premature dismissal in January 2015. Both took the stand today and provided absolutely damning testimony. They disclosed that their investigation turned up serious defects in the original investigation, significant evidence to support the claim that it was William Holmes, Jason Wallace, Rashan Brown, Shelmar Johnson, and Marquez Pennington who killed a young John Hartman in 1997 – the very crime for which the Fairbanks Four were convicted and have maintained innocence for and fought 18 long years to bring back to court. Frese attorney Jahna Lindemuth asked Trooper McPherron if their investigation produced any evidence that the Fairbanks Four were present when Hartman was assaulted, McPherron simply answered, “No.”

But the two investigators testimony about the deficits in their own investigation cast harsh light onto the current approach and practices of the State of Alaska and the prosecutors who are defending the faulty convictions. Gallen and McPherron revealed that Special Prosecutor Adrienne Bachman instructed them not to collect a specific and exonerating statement from a witness who had heard a confession from Marquez Pennington, a man named as one of the fellow Hartman killers by Holmes. They also testified that prosecutors and police hid the Torquato memo and the fact that they had received and failed to respond to a confession from Holmes in 2011. Bachman, they claimed, refused to hand over emails between herself and Officer Jim Geier, a man heavily involved in the original investigation as well as alleged efforts to downplay or hide significant exonerating evidence that emerged from the time of the initial investigation through 2015.

A particularly cringe-worthy exchange between Bachman and one of her former investigators occurred when the trooper described how he, Bachman, and McPherron had tested the Olson testimony by attempting to identify each other from the distance Olson described in his testimony. Gallen stated that they had been unable to distinguish even the most basic identifying details of appearance at that distance. Bachman remarked that the troopers failed to indicate in their report that she had been able to make an ID from that distance.

“You did not indicate that to me,” Gallen replied.

Bachman only scoffed in response, and Gallen continued, “all you said was ‘O my God, oh my God, and I didn’t know what you meant by that.”

Gallen and McPherron also testified that they were removed from the case before their investigation was complete. Their demeanor toward Bachman was palpably hostile, and accusations of inappropriate conduct on behalf of the special prosecutor were peppered amongst the testimony condemning the convictions of the Fairbanks Four.

Bachman had indicated during opening statements that the state’s investigation confirmed the original convictions. Testimony from her own investigators today not only failed to confirm that, but undermined absolutely every facet of the case, from the integrity of the original convictions, the police work that led to them, the prosecution of the original cases, bolstered the alternate suspect theory, and cast significant doubt as to the intention and honesty of the State effort led by Bachman to defend the convictions. These should have been the state’s star witnesses, and instead they proved catastrophic to the state’s case. The local reputation of Alaska State Troopers is indeed one of independence, and in general they are locally perceived as more trustworthy than other branches of the Alaska justice system. Today’s testimony certainly affirmed that the troopers reached their own conclusions without inappropriate consideration to the politics of the case, a welcome first for supporters of the Fairbanks Four.

Bachman had indicated during opening statements that the state’s investigation confirmed the original convictions. Testimony from her own investigators today not only failed to confirm that, but undermined absolutely every facet of the case, from the integrity of the original convictions, the police work that led to them, the prosecution of the original cases, bolstered the alternate suspect theory, and cast significant doubt as to the intention and honesty of the State effort led by Bachman to defend the convictions. These should have been the state’s star witnesses, and instead they proved catastrophic to the state’s case. The local reputation of Alaska State Troopers is indeed one of independence, and in general they are locally perceived as more trustworthy than other branches of the Alaska justice system. Today’s testimony certainly affirmed that the troopers reached their own conclusions without inappropriate consideration to the politics of the case, a welcome first for supporters of the Fairbanks Four.

There remains absolutely no indication that the State of Alaska has changed their strategy, and it appears that they will move forward with attacking the post conviction relief proceedings based on technicalities and hopes to declare much of the exonerating evidence inadmissible. Alaska State Governor Bill Walker has remained conspicuously silent as the State spends untold millions on a conviction even their own investigators believe is wrongful. Meanwhile, two known child killers are free on the streets of Fairbanks, presuming they have not fled, which may be Alaskan’s best hope for safety from the men, and there is no indication whatsoever that the State plans to pursue them despite the growing mountain of evidence that they committed one of the most heinous crimes in the history of the “Golden Heart City.”

Read this story in our local news!