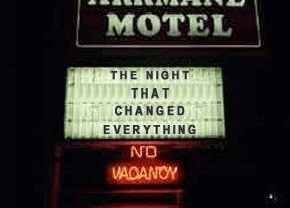

On the same evening that John Hartman lived his last night on Earth, four other young men also spent a normal day with their friends and families, with no idea as evening fell that October 10, 1997 would be the last normal day. No premonition that the night and early morning hours of October 11, 1997 would contain the moments that changed their lives forever; the line that now divides their lives into two parts – before and after.

On the same evening that John Hartman lived his last night on Earth, four other young men also spent a normal day with their friends and families, with no idea as evening fell that October 10, 1997 would be the last normal day. No premonition that the night and early morning hours of October 11, 1997 would contain the moments that changed their lives forever; the line that now divides their lives into two parts – before and after.

None could have possibly predicted that each movement they made would be scrutinized for a decade and more. Not one of the looked into the faces of those around them knowing that these friends, family members, acquaintances, and strangers were about to become alibis. That some of them would be threatened, that some of them would be courageous, that some would be afraid, that some would become activists, that some would sink into their sorrow. No. It was an ordinary night.

The four boys knew each other. They were not close friends, but had all played on the same basketball team for Howard Luke, a predominantly Native high school. They did not spend the evening together, but each saw the others at least for a moment at some point that evening. The times their paths crossed that evening they would not have known that soon they were to be each others only friends – the only familiar faces in a foreign place, and an all encompassing nightmare.

The Four Were:

Marvin Roberts. Marvin was 19, had been valedictorian of his class that spring, a basketball enthusiast, a doting older brother to his toddler brother, and best friends with his sister. A gentle person. He was not a drinker, and unlike most of his classmates and friends, had a car.

Eugene Vent. Eugene was 17 that fall and a basketball enthusiast. He was funny guy, always smiling, and kind. He was young, and like many young men he drank too much and too often. He had, just days prior, revived a ticket for drinking underage. Like so many other teenage boys Eugene was finding his way from boyhood to manhood, a road not without challenges, but on the whole was a good guy.

George Frese. George was 20 at the time, and the oldest of the four. He was a doting father to his three year old daughter Tiliisia, and most who knew him at this time will talk first of his dedication to his daughter. George and his partner faced challenges common for teenage parents, but met most of them with grace. George did not drink often, but when he did he drank to great excess

Kevin Pease. Kevin was 19, smart, an athlete, and a kid who was doing his best to transcend hardships at home. His father had been murdered just a short time before this pivotal night. One friend, asked to describe Kevin, said “Fun. Brave. But if I had one word I would say fun. It was hard not to smile when Kevin smiled.” Kevin had had a series of small run-ins with the police. He was the baby of his family.

Kevin Pease. Kevin was 19, smart, an athlete, and a kid who was doing his best to transcend hardships at home. His father had been murdered just a short time before this pivotal night. One friend, asked to describe Kevin, said “Fun. Brave. But if I had one word I would say fun. It was hard not to smile when Kevin smiled.” Kevin had had a series of small run-ins with the police. He was the baby of his family.

How they spent that fateful night:

Marvin spent the bulk of the night at a wedding reception, where many tens of people saw him throughout the evening. He was the only one of the four that did not get drunk that night. Earlier in the evening he cruised around aimlessly with a few friends, looking for girls. He gave a few people rides. No less that 10 people insist that they saw him dancing and mingling between the hours of 1 am and 2am.

That night, Kevin and Eugene went to a house party in the hills above Fairbanks. Their friend had the house to himself with his parents out if town, and the predictable party and mayhem followed. A house party full of people of course saw them at the party, drinking and mingling. Both Kevin and Eugene drank heavily; Eugene drank to the point that he blacked out much of the night. A sober driver eventually drove a car packed with teenagers like sardines back toward town. He remembers looking at the clock frequently he says, because he was nervous about getting pulled over with a car full of drunk teenagers out past legal curfew. He says that the arrived in town at about 2am. This is notable because it is a full half hour after John Hartman was attacked.

Once in town, they stopped by the wedding reception, and ultimately went their separate ways, with Eugene heading to a part in a room at the Alaska Motor Inn and Kevin heading home.

George spent the first part of the night at home drinking with some friends and his girlfriend Crystal. Three sober babysitters watched George and Crystal’s daughter while they visited with their company. Another sober friend, the late Patrick Henry, older brother of Edgar Henry, said he was with George and his little brother all night. He says that they left George’s apartment as a group at about 1:30am, and walked as a group first to a friend’ s house, and then to the large wedding reception downtown. He said his brother and George were so drunk he had to “babysit” them, and consequently remembers their actions that night well. He says they arrived a the reception at 2am, and were together until after 3am.

How did they become suspects?

Eugene was arrested first, walking home from the part at Alaska Motor Inn. He ran when the police car pulled up on him, which they considered the first indication of his guilt. In reality, he ran because he was a young drunk kid, and the police were behind him. Clearly, his whole life would be different if he had run faster.

Kevin was brought in next. When he got home to is mother’s house, they had a huge fight, and he smashed up the house – punched Sheetrock, broke a few things. His mother called the police, a decision that she went to her death-bed regretting. He was a teenage troublemaker, already known to the police. When they realized he knew Eugene, a theory began to develop.

George was the third one taken. He woke up the next day still drunk and with a hurt foot. He was limping around in it complaining, and went to the E.R. to have it looked at. An ER nurse who had treated both the white boy dying upstairs and the Native boy with a hurt foot downstairs decided that the two patients were linked and alerted police. At some point the police did enough research to determine that George had played on the same high school basketball team as Eugene and Kevin. They came to the hospital for him.

Marvin was last. They showed up at his home, where he was sitting with an uncle, and took him in for questioning. During his interrogation he said he was innocent dozens of times, apologizing when an officer accused him of being disrespectful for saying it, and calling both officers “sir” through the entire interview, but never wavered for a moment in his insistence that they had the wrong person. Marvin was in that same yearbook photo, and probably the only one who had managed to get a car since graduation, and for the scenario that the police were building there had to be a driver.

A child was murdered at 1:30am, at which time four Indian boys were dancing at a wedding, walking to a friend’s house, and driving in a car packed like a sardine can. Yet, by the next morning the police are taking a victory lap for the local press, theorizing that these Indians probably killed the kid because he was white, or else that it is simply in their savage nature.

If you have read this far, you are likely left with nothing but questions, most of which boil down to why and how. If what we wrote above is true, and it is, why did they arrest these four men? Why were these alibis discounted? How were they convicted?

The answers can be long, or they can be short. The short answers are that they were arrested by chance, and guilty of being Native before the first question came. That they were drunk, terrified, with no idea what their actual legal rights were since they were not raised in the Law and Order culture, but the culture of Interior Alaska, where in the late 90’s most Native kids understood that once the cops picked you up whatever came next was up to the cops, and that resistance made things worse.

Their alibis were dismissed as not reliable, because their alibis were Indians. The D.A.’s closing argument was that, much like in the “I am Spartacus” scene, that Natives will lie for Natives, take care of their own kind, and can’t be trusted. Similar to the decrees long issued in this country that the savage is different.

They were convicted in puppet show trials by juries not made of their peers, with no physical evidence, and plenty of corruption. And the trials didn’t matter. Despite the fact that no one here had ever seen any prisoner from Fairbanks Correctional costumed that way before, they marched them out chained together and dressed in orange for their arraignment. The public defender of course voiced his shock and called it grandstanding, but it was too late. The picture was snapped of the four chained together in orange, and it would run beside the smiling school picture of a victim that could be anyone’s child in every early article and news story run in Alaska and was the stock image for years to come. And the story, see, made sense. It didn’t have to make factual sense to make sense in the hearts of many. The official statement may as well have been, “Four Indians savagely killed a child, because he was white. No one’s children were safe, but now they are. We are protecting you from a fear you felt but could never substantiate. There will be no further questions.” They didn’t come up with any motivation beyond hoping that the public would assume these four were just senselessly violent people.

They were convicted in puppet show trials by juries not made of their peers, with no physical evidence, and plenty of corruption. And the trials didn’t matter. Despite the fact that no one here had ever seen any prisoner from Fairbanks Correctional costumed that way before, they marched them out chained together and dressed in orange for their arraignment. The public defender of course voiced his shock and called it grandstanding, but it was too late. The picture was snapped of the four chained together in orange, and it would run beside the smiling school picture of a victim that could be anyone’s child in every early article and news story run in Alaska and was the stock image for years to come. And the story, see, made sense. It didn’t have to make factual sense to make sense in the hearts of many. The official statement may as well have been, “Four Indians savagely killed a child, because he was white. No one’s children were safe, but now they are. We are protecting you from a fear you felt but could never substantiate. There will be no further questions.” They didn’t come up with any motivation beyond hoping that the public would assume these four were just senselessly violent people.

The LONG answers? Will be here, in this blog, and are partially addressed in the links below. You do not have to take our word for it, because we wouldn’t expect you to, and because we don’t need you to. All we ask is that you remain, hear this story, and take from it what you will.

If you want to do further reading, please take a moment to look at the work of journalist Brian O’Donoghue and the UAF Journalism Department Students via their website, or the “Decade of Doubt” series that ran in the local paper.