Alaska. The tourists come here in buzzing clouds, thick and as transient as mosquitos. They are very old. They are in the twilight of their lives. The women have poofs of white hair and wear elastic banded blue jeans. Their husbands carry cameras and wear khaki explorer hats.They arrive on enormous cruise ships and travel the thin highways on guided bus tours and train tracks, led by bright-eyed college students spending their summer working as tour guides. The greatest generation, spending their carefully sequestered Alaska portion of their retirement account, shuffling on the gravel at every highway overlook, scanning the horizons with their binoculars in search of a bear, a moose, their history. They all buy the same deep blue sweatshirt that says “Alaska: The Last Frontier,” in gold-embroidered letters. It is, after all, why they came – to see the Last Frontier. It calls to them because they come from places where the frontier has been conquered and settled and is gone now. Alaska is the last, the very last, American frontier.

There is a lot of magic in a name; part truth and part spell. The Last Frontier was bestowed carefully, a tribute both to the land’s untamed expanses and America’s deep rooted nostalgia for the era of cowboys sleeping under the stars and teepees peppering the wide open plains. America misses the Last Frontier. The idea that our ancestors walked bravely into the unknown, carved trails through an unforgiving wilderness, and ultimately weaved from the fabric of drastically different cultures, hard work, and luck the world’s strongest country is a great story. Our story. It is written so deeply into our collective consciousness that we walk with it, always, so intrinsic that we forget it is there. All of those old men and women were children once, together in that November classroom to learn the story. We were all there. When winter began to bite through fall we carefully stapled together the wide brown band of construction paper and pasted bright feathers to our Indian head-dress. We glued the bright yellow paper buckle to our pilgrim hats while the teacher laid out the multi-colored corn and parents arrived for the feast. And there, divided only by our different paper hats, we acted out the story: pilgrims and Indians eating together. Pilgrims and Indians celebrating abundance, welcoming the winter, waiting for the thaw, for the spring when America would begin in earnest. Thankful. So very deeply thankful for not just a meal, but for what was to come.

The story of our bright beginning, the purest freedoms, the wide open plains, that story is deep in our bones now. But we know that it wasn’t that easy. We feel the ghosts of other, less often told stories, lurking in the periphery of that happy story. We close our eyes and see teepees burning. We know that the pilgrims won, and we know how. Sand Creek. Custer’s Last Stand. Trails and trails of blood and tears carved through what was the frontier, paved and perfected so that the wild could become America. We sense it – that when those early November’s frost chased away the last of the leaves and winter was moments away, thousands of children were placed in hard-dug graves, wheels of wagons crashed over tiny bones and ground them to dust, and the division was real. Some of us walk with those stories, too, as deeply written and as impossible to shed as the first Thanksgiving. But those stories are heavier. Harder to carry.

For most of America, the stories get further away each season, until they are so far in the distance they are forgotten. The terrible ones remain untold until the words are hard to form and people are able to forget. But this is the Last Frontier, and here, the wagons must keep moving if America is to take root properly. Here it is sometimes America of golden arches and great bridges, but much of the time it is still cowboys and Indians.

In Alaska we are plagued with a terrible double vision, one we cannot make peace with. See, this is the America that learned from its past. This is the country that has progressed, where a million men marched, where a woman would not budge from her bus seat, where we can erradicate the past in order to form a more perfect union. And Alaska is part of that America. Yet, we are out of time in some ways. We are not as far along in our story, we are somehow still in the part where teepees must be burned and trails must be carved, even though we know the ending, even though McDonald’s is here before all the bison are dead. We are American enough that we believe ourselves to not be racist, to believe ourselves to be undivided. But when Martin Luther King had a dream, soldiers still came in the night to take Indian children out of their beds and send them away. Not a story from our ancestors, a story from our parents. It’s all wrong. Someone forgot to divide the Indians into reservations and erect copper likenesses of their murdered chiefs in the town squares. Someone forgot to build town squares. We are not divided enough to pretend convincingly that we are undivided. So, we have to play a kind of first Thanksgiving. America lays out the feast and shows us the colorful corn that could never grow in this soil. See here? America says. The proof that this is your story, too. Our story together. And we put on our technicolor feathers and flopping construction paper buckles and rehearse our happy meal. Pilgrims and Indians, cowboys and Indians, make believe until you believe.

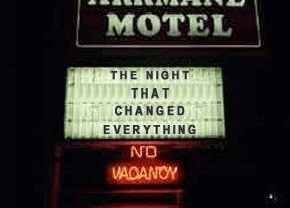

Then, sometimes, something happens that breaks it all back open and the other stories come roaring alive. A boy, say, scalped on the streets, his blood staining snow, the last of his hot breath wisping into the late fall sky, life leaving him.

Men in cars with red and blue flashing lights, wearing badges and those black paper hats that were placed onto their heads so long ago that they have forgotten they are there. Still, right away they scan the horizon, begin looking for four Indian boys playing at warrior games, feathers like a shadow. The investigation is over now, before it has begun, because these men remember this story. They know how it ends already.

This story is very old. This is the story of America. This is the story of the Last Frontier, the very last. This is a story that you know already. This story was whispered to you once in the rustling of construction paper and dried corn. This is a sad story. Listen, listen.